Pàgina: 2 : 1

Catre Louise si Fraces Norrcros

: sfarsitul lui aprilie 1873

Personales 2005-01-16 (10413 senalas) Personales 2005-01-16 (10413 senalas)

22

:

Poemas 2005-11-27 (11131 senalas) Poemas 2005-11-27 (11131 senalas)

288

: (traducere in italiana de Augusto Sabbadini)

Poemas 2005-10-25 (11905 senalas) Poemas 2005-10-25 (11905 senalas)

A Word is Dead

:

Poemas 2005-06-21 (15787 senalas) Poemas 2005-06-21 (15787 senalas)

A word is dead

:

Poemas 2008-11-15 (10187 senalas) Poemas 2008-11-15 (10187 senalas)

Această țărână tăcută a fost domni și doamne

: Traducere în limba română de Leon Levițchi și Tudor Dorin

Poemas 2009-06-27 (11471 senalas) Poemas 2009-06-27 (11471 senalas)

Adu-mi apusul de soare-ntr-o cupă

: Bring me the sunset in a cup

Poemas 2005-07-19 (15649 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-19 (15649 senalas)

Am simțit o Înmormîntare În Creier

: I felt a Funeral in my Brain

Poemas 2005-07-18 (15214 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-18 (15214 senalas)

Am văzut o privire în agonie

:

Poemas 2006-07-28 (14698 senalas) Poemas 2006-07-28 (14698 senalas)

Apa se învață prin sete

: Water is taught by thirst

Poemas 2005-07-21 (16822 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-21 (16822 senalas)

Aur arzând în purpur scăldat

: Traducere în limba română de Leon Levițchi și Tudor Dorin

Poemas 2009-06-27 (11413 senalas) Poemas 2009-06-27 (11413 senalas)

Bătuse vântul ca un om trudit

: Traducere în limba română de Leon Levițchi și Tudor Dorin

Poemas 2009-06-27 (11457 senalas) Poemas 2009-06-27 (11457 senalas)

Bello è sentirsi cercare

:

Poemas 2005-08-31 (13753 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-31 (13753 senalas)

Biblia este un antic volum

:

Poemas 2009-08-13 (11767 senalas) Poemas 2009-08-13 (11767 senalas)

Când piezișă cade raza

: Traducere în limba română de Leon Levițchi și Tudor Dorin

Poemas 2009-06-27 (11605 senalas) Poemas 2009-06-27 (11605 senalas)

Ce fericită-i piatra mică

: Traducere în limba română de Leon Levițchi și Tudor Dorin

Poemas 2009-06-27 (11463 senalas) Poemas 2009-06-27 (11463 senalas)

Cîte Flori neștiute în Pădure rămîn

: How many Flowers fail in Wood

Poemas 2005-08-03 (15046 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-03 (15046 senalas)

Cunosc vieți, de care m-aș lipsi

: I know lives, I could miss

Poemas 2005-08-20 (15119 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-20 (15119 senalas)

Cuvîntul e mort

: A word is dead

Poemas 2005-07-21 (14645 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-21 (14645 senalas)

De mi-a fost gazdă ori oaspete mi-a fost

: He was my host - he was my guest

Poemas 2005-08-17 (14371 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-17 (14371 senalas)

Deunăzi - îmi rătăcisem Lumea

: I lost a World

Poemas 2005-07-22 (14880 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-22 (14880 senalas)

Dimineața e pentru Rouă

: Morning is the place for Dew

Poemas 2005-07-27 (14834 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-27 (14834 senalas)

Din Cupe adîncite în Perlă

: I taste a liquor never brewed

Poemas 2005-07-23 (14742 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-23 (14742 senalas)

Doriți Vară? Gustați-o pe a noastră

: Would you like summer? Taste of ours

Poemas 2005-08-23 (16732 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-23 (16732 senalas)

După o mare durerre urmează nepăsarea

: After a great pain

Poemas 2005-08-12 (15300 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-12 (15300 senalas)

După-o mare durere, urmează o senzație solemnă

: Traducere în limba română de Leon Levițchi și Tudor Dorin

Poemas 2009-06-27 (11720 senalas) Poemas 2009-06-27 (11720 senalas)

E ușor să muncești cînd sufletul se joacă

: It is easy to work when the soul is at play

Poemas 2005-07-27 (14859 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-27 (14859 senalas)

Era prea tîrziu pentru Om

: It was too late for Man

Poemas 2005-08-08 (13470 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-08 (13470 senalas)

Eu am murit pentru frumusețe

:

Poemas 2003-09-29 (13692 senalas) Poemas 2003-09-29 (13692 senalas)

Eu n-am pierdut decît de două ori

: I never lost as much but twice

Poemas 2005-07-18 (14470 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-18 (14470 senalas)

Eu neștiind când or să vină zorii

:

Poemas 2003-09-29 (12964 senalas) Poemas 2003-09-29 (12964 senalas)

Eu Nimeni sunt! Tu cine ești?

: I'm Nobody! Who are you?

Poemas 2005-07-27 (26763 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-27 (26763 senalas)

Eu nu pot trăi cu tine

:

Poemas 2009-05-17 (11296 senalas) Poemas 2009-05-17 (11296 senalas)

Exaltarea este drumul

:

Poemas 2005-07-21 (12826 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-21 (12826 senalas)

Exclusion

:

Poemas 2004-10-10 (12171 senalas) Poemas 2004-10-10 (12171 senalas)

Există oare "Dimineața" cu adevărat?

: Will there really be a "Morning"

Poemas 2005-07-18 (14038 senalas) Poemas 2005-07-18 (14038 senalas)

Flocons de neige

:

Poemas 2017-07-02 (7698 senalas) Poemas 2017-07-02 (7698 senalas)

Hope is a thing with feathers:

:

Poemas 2006-10-14 (12871 senalas) Poemas 2006-10-14 (12871 senalas)

I cannot live with You

:

Poemas 2006-02-11 (11237 senalas) Poemas 2006-02-11 (11237 senalas)

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain

: (280)

Poemas 2002-09-15 (13114 senalas) Poemas 2002-09-15 (13114 senalas)

I GAVE myself to him

: 22

Poemas 2002-09-18 (10845 senalas) Poemas 2002-09-18 (10845 senalas)

I HIDE myself within my flower

: 7

Poemas 2002-09-18 (10843 senalas) Poemas 2002-09-18 (10843 senalas)

I like a look of agony

:

Poemas 2005-06-12 (10351 senalas) Poemas 2005-06-12 (10351 senalas)

Iată-mi scrisoarea către Lume

: This is my letter to the World

Poemas 2005-08-17 (14276 senalas) Poemas 2005-08-17 (14276 senalas)

If I should die

:

Poemas 2004-06-24 (16303 senalas) Poemas 2004-06-24 (16303 senalas)

În ochii mei - atât de jos a căzut

: Traducere în limba română de Leon Levițchi și Tudor Dorin

Poemas 2009-06-27 (11104 senalas) Poemas 2009-06-27 (11104 senalas)

Pàgina: 2 : 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

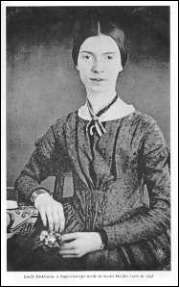

Biografía Emily Dickinson

Elizabeth Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830 in the quiet community of Amherst, Massachusetts, the second daughter of Edward and Emily Norcross Dickinson. Emily, Austin (her older brother) and her younger sister Lavinia were nurtured in a quiet, reserved family headed by their authoritative father Edward. Throughout Emily’s life, her mother was not "emotionally accessible," the absence of which might have caused some of Emily’s eccentricity. Being rooted in the puritanical Massachusetts of the 1800’s, the Dickinson children were raised in the Christian tradition, and they were expected to take up their father’s religious beliefs and values without argument. Later in life, Emily would come to challenge these conventional religious viewpoints of her father and the church, and the challenges she met with would later contribute to the strength of her poetry.

The Dickinson family was prominent in Amherst. In fact, Emily’s grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, was one of the founders of Amherst College, and her father served as lawyer and treasurer for the institution. Emily’s father also served in powerful positions on the General Court of Massachusetts, the Massachusetts State Senate, and the United States House of Representatives. Unlike her father, Emily did not enjoy the popularity and excitement of public life in Amherst, and she began to withdraw. Emily did not fit in with her father’s religion in Amherst, and her father began to censor the books she read because of their potential to draw her away from the faith.

Being the daughter of a prominent politician, Emily had the benefit of a good education and attended the Amherst Academy. After her time at the academy, Emily left for the South Hadley Female Seminary (currently Mount Holyoke College) where she started to blossom into a delicate young woman - "her eyes lovely auburn, soft and warm, her hair lay in rings of the same color all over her head with her delicate teeth and skin." She had a demure manner that was almost fun with her close friends, but Emily could be shy, silent, or even depreciating in the presence of strangers. Although she was successful at college, Emily returned after only one year at the seminary in 1848 to Amherst where she began her life of seclusion.

Although Emily never married, she had several significant relationships with a select few. It was during this period following her return from school that Emily began to dress all in white and choose those precious few that would be her own private society. Refusing to see almost everyone that came to visit, Emily seldom left her father’s house. In Emily’s entire life, she took one trip to Philadelphia (due to eye problems), one to Washington, and a few trips to Boston. Other than those occasional ventures, Emily had no extended exposure to the world outside her home town. During this time, her early twenties, Emily began to write poetry seriously. Fortunately, during those rare journeys Emily met two very influential men that would be sources of inspiration and guidance: Charles Wadsworth and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. There were other less influential individuals that affected Emily, such as Samuel Bowles and J.G. Holland, but the impact that Wadsworth and Higginson had on Dickinson were monumental.

The Reverend Charles Wadsworth, age 41, had a powerful effect on Emily’s life and her poetry. On her trip to Philadelphia, Emily met Wadsworth, a clergyman, who was to become her "dearest earthly friend". A romantic figure, Wadsworth was an outlet for Emily, because his orthodox Calvinism acted as a beneficial catalyst to her theoretical inferences. Wadsworth, like Dickinson, was a solitary, romantic person that Emily could confide in when writing her poetry. He had the same poise in the pulpit that Emily had in her poetry. Wadsworth’s religious beliefs and presumptions also gave Emily a sharp, and often welcome, contrast to the transcendentalist writings and easy assumptions of Emerson. Most importantly, it is widely believed that Emily had a great love for this Reverend from Philadelphia even though he was married. Many of Dickinson’s critics believe that Wadsworth was the focal point of Emily’s love poems.

When Emily had a sizable backlog of poems, she sought out somebody for advice about anonymous publication, and on April 15, 1862 she found Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an eminent literary man. She wrote a letter to Higginson and enclosed four poems to inquire his appraisal and advice.

Although Higginson advised Dickinson against publishing her poetry, he did see the creative originality in her poetry, and he remained Emily’s "preceptor" for the remainder of her life. It was after that correspondence in 1862 that Emily decided against publishing her poems, and, as a result, only seven of her poems were published in her lifetime - five of them in the Springfield Republican. The remainder of the works would wait until after Dickinson’s death.

Emily continued to write poetry, but when the United States Civil War broke out a lot of emotional turmoil came through in Dickinson’s work. Some changes in her poetry came directly as a result of the war, but there were other events that distracted Emily and these things came through in the most productive period of her lifetime - about 800 poems.

Even though she looked inward and not to the war for the substance of her poetry, the tense atmosphere of the war years may have contributed to the urgency of her writing. The year of greatest stress was 1862, when distance and danger threatened Emily's friends - Samuel Bowles, in Europe for his health; Charles Wadsworth, who had moved to a new pastorate at the Calvary Church in San Francisco; and T.W. Higginson, serving as an officer in the Union Army. Emily also had persistent eye trouble, which led her, in 1864 and 1865, to spend several months in Cambridge, Mass. for treatment. Once back in Amherst she never traveled again and after the late 1860s never left the boundaries of the family's property.

The later years of Dickinson’s life were primarily spent in mourning because of several deaths within the time frame of a few years. Emily’s father died in 1874, Samuel Bowles died in 1878, J.G. Holland died in 1881, her nephew Gilbert died in 1883, and both Charles Wadsworth and Emily’s mother died in 1882. Over those few years, many of the most influential and precious friendships of Emily’s passed away, and that gave way to the more concentrated obsession with death in her poetry. On June 14, 1884 Emily’s obsessions and poetic speculations started to come to a stop when she suffered the first attack of her terminal illness. Throughout the year of 1885, Emily was confined to bed in her family’s house where she had lived her entire life, and on May 15, 1886 Emily took her last breath at the age of 56. At that moment the world lost one of its most talented and insightful poets. Emily left behind nearly 2,000 poems.

As a result of Emily Dickinson’s life of solitude, she was able to focus on her world more sharply than other authors of her time - contemporary authors who had no effect on her writing. Emily was original and innovative in her poetry, most often drawing on the Bible, classical mythology, and Shakespeare for allusions and references. Many of her poems were not completed and written on scraps of paper, such as old grocery lists. Eventually when her poetry was published, editors took it upon themselves to group them into classes - Friends, Nature, Love, and Death. These same editors arranged her works with titles, rearranged the syntax, and standardized Dickinson’s grammar. Fortunately in 1955, Thomas Johnson published Dickinson’s poems in their original formats, thus displaying the creative genius and peculiarity of her poetry.

Emily Dickinson wrote a total of 1,775 poems. Since none but a handful of them were published during her own lifetime, there is no easy way to arrange them. With other poets you group their work by what publication they come from, or by what year they first saw print, or perhaps by ordering the titles of the poems alphabetically. None of this can be applied to Emily's poetry, not even alphabetically by title, since she didn't title her poems.

In 1955 a three-volume critical edition edited by Thomas H Johnson set a new standard for Emily Dickinson students and scholars the world over. The book compiled all the 1,775 poems in chronological order (as far as could be ascertained). Not only that, but the poems were finally published in their original form, uncorrupted by decades of intrusive editors.

|